World On A Silver Platter

A Brief History of Optical Disc

by

David Robert Cellitti

This article was originally published in Widescreen Review's Laser Magic 1998 Guide

and is reprinted here by permission of the author.

|

Introduction

In the fall of 1991, I wrote a small article concerning MCA DiscoVision, the very first LaserDiscs

available to the public. During the final edit, the publisher asked me to clear up a matter of ownership between MCA,

Phillips, IBM and Pioneer. It was a little unclear as to who was involved and when in the article. This relatively

simple request was the beginning of a personal odyssey that I am still on to this day.

This article covers the specific time period between 1958, when David Paul Gregg first conceived of

the idea and coined the name "video disc" until 1989, when the original commercial producers of the medium decided to

abandon the project and turned the industry over to Pioneer.

When I first began this project I found that there was very little documentation concerning

the origins of optical storage and that, what little there was, was often inaccurate, incomplete or slanted in one

corporate direction or another.

In his book "Opening Minds: the Evolution of Videodiscs An Interactive Learning" (Kendall/Hunt

Publishing 1989), George R. Hayes begins videodisc history with a German engineer by the name of Paul Nipkow. Nipkow

patented a disc process in 1884, which created visual images by using a mechanical scanning process. Next, we come to

John Logie Baird, a Scotsman who, in the early 1930's, pressed shellac phonograph records that could transmit "a dozen

grainy still images" on his Baird Television receiver so that potential customers could tune in their sets in anticipation

of BBC broadcasts. Haynes, as well as some of the people I interviewed, also cites French inventor P.M.G. Toulon as an

early developer of the video disc. Toulon filed patents in 1952 for a system using a photographic method of producing

discs. Although no system seems to have ever been produced, the patents were finally issued to him in 1965.

In the 1984 "Videodisc Book: A Guide and Director" (J. Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York), author Rod Daynes credits Baird and his 1926 Phonovision, then names Wayne Johnson, David Paul Gregg and Dean DeMoss as the 3M triumvirate responsible for developing the first optical disc in the early 1960's.

Close, but no cigar.

The following history is not meant to be definitive in any way. It is, however, the distillation of

over eight years of research and represents dozens of interviews and hundreds of hours of investigation into the roots of

optical storage. For most of you already heavily invested in CDs, LDs and DVDs, I'm sure it will be the first (but

hopefully not the last) time that you'll hear anything about the true origins of this most amazing medium.

Ground Zero - David Paul Gregg and 3M Mincom

Following the end of World War II, an ex-Army core engineer by the name of Jack Mullin began making the rounds in the business community to try and find backing for the manufacturing of magnetic audio tape recorders. Mullin was part of a handful of people who had managed to get their hands on tape heads produced by the Germans during the Nazi regime, which were far superior to anything coming out of America. One of the people Mullin contacted was Frank Healey, a talent agent who counted crooner Bing Crosby among his numerous Hollywood clients. Crosby, one of America's most popular and prolific singers, hosted a popular radio show that was routinely recorded on shellac discs for broadcast. It seems Crosby loathed live broadcasts, was known for his ribald adlibs and liked his time kept as free as possible. By pre-recording the show on discs, the ribald comments could be edited out, the show kept tight and Crosby's time was then his own.

However, the process was labor intensive, crude and the broadcast quality of the marginal at

best. Once Healey set up a demonstration for Crosby of Mullin's remarkable recording and playback equipment, the

die was cast. Crosby was an astute businessman and knew that any technology developed by him would most certainly

be absorbed into the lucrative film and budding television industry. Bing Crosby Enterprises was immediately formed

in order to develop, promote, and sell magnetic recording equipment with Healey as President and Mullin on board as

Chief Engineer.

Crosby Enterprises was a complete success and sales of machines and tape (supplied by 3M Corporation) was brisk. Crosby and his engineers had an eye to the future and everyone knew that the next barrier to cross would be videotape. The engineers enlisted by Mullin to help in developing Crosby Enterprises were Dean DeMoss and Wayne Johnson, two names that would eventually be linked to video disc history.

The fate of videotape and Crosby Enterprises is best documented in the book "Fast Forward" by James Lardner (1987, Norton Press). All that one needs to know is that by the very early sixties it was apparent to all that the Northern California-based company Ampex was the winner in the race to perfect videotape, not Crosby Enterprises. Crosby, knowing that the battle was lost, took the opportunity to cut his losses and sold his company to 3M, where it was absorbed into the Minnesota conglomerate and renamed Mincom.

Four major projects were to sprout at Mincom - Project A, Project B, Project C and Project D. The fourth, Project D, was a mandate from 3M for Mincom engineers to explore the feasibility of producing a low cost video disc system that could be marketed as a consumer product.

From whence did Project D spring?

David Paul Gregg, an "eclectic engineer" (his words), claims that he first conceived of the name

and concept of video disc during his employment at Westrex corporation in the late 1950's. It was while at Westrex that

Gregg claims he realized it would be possible to burn video and audio information onto a disc master, encoding an FM

signal through a series of pits. A stamper could then be made from this master and copies pressed for consumer sales.

Playback of information would be accomplished by using a concentrated light source that would decode the signals and pump

them onto a video monitor for home viewing.

While at Westrex, David Paul Gregg had become friends with a man by the name of Chuck Tobias. When Gregg was terminated from Westrex in 1960, it was Tobias (now working in sales at Mincom) who introduced David Paul Gregg to Mincom President Frank Healey as "Mr. Videodisc." 3M was on an active quest to develop new hardware and software for the consumer market and Healey, impressed with Gregg's idea, decided to bring him on board.

David Paul Gregg only lasted three months at Mincom. The scenario that was to play itself out during his stay there was a pattern that haunted him for the rest of his career and eventually robbed him of any chance to see his invention to fruition.

From the beginning, it was apparent that Gregg was extremely paranoid about someone taking his video disc baby away from him. Contemporaries of Gregg tend to portray him as a loner, highly volatile and not a team player. A square individual peg unable or unwilling to fit into any corporate round hole.

Conflict between David Paul Gregg and Healey was immediate. Healey, sensing that Gregg's stay at Mincom would be short, appears to have hedged his bets concerning video disc by secretly going to Stanford Research Institute (SRI) behind Gregg's back for input concerning the project.

Gregg went ballistic when he discovered that the project was being farmed out and, sensing

that he was about to loose control of video disc, decided to leave 3M. One contemporary clearly remembers Gregg coming

in on a Sunday, packing his things, throwing them into the back of his truck and leaving. In any event, the parting

was not amicable, but the seed was sown and Healey moved forward with the project without Gregg. Mincom eventually

produced a prototype player, replicated discs and was awarded nineteen patents that were to form the core of the 3M

video disc patent package. Three of these specifically name Gregg as either author, or co-author, thereby marking

is participation in the project. Gregg was eventually brought back in for a time as a consultant to 3M, but was

neither privy to nor included in on anything to do with Project D nor asked for any further input concerning video disc.

Winston Research and Gauss Electrophysics

While under the Crosby Enterprises wing, engineers at Mincom were pretty much given a free hand to do as they pleased. The end product and sales was all that mattered. As the corporate roots of 3M grew deeper and deeper into the labs, things became more structured and consequently more restrictive for the engineers. The end result was that in 1965 there was a mass exodus of some of the key Mincom staff over to a new company formed by Gregg's old friend Chuck Tobias called Winston Research.

Gregg insists that video disc research was the primary reason for Winston's formation. It is

the recollection of almost everyone else that Winston was formed so that they could go into direct competition with

3M with a new brand of magnetic tape recorders.

Whatever the truth, Gregg became part of Winston Research Corporation, and it was there that he was to meet and work with Keith O. Johnson, a brilliant young engineer and graduate from Stanford University who had been wooed away from Ampex in order to work at Winston.

No sooner was Winston up and running when 3M slapped the company with a lawsuit claiming that departing engineers from Mincom had taken company specifications to produce the audio hardware now being marketed by Winston.

The legal expenses were to eventually sink Winston and topple Frank Healey as head of Mincom, but

the suit, which went on for years, was to be a touchstone for all future cases concerning intellectual property rights in electronics.

Gregg, concerned that nothing was being done at Winston regarding the development of his video disc and mindful of the monolithic war being waged by 3M, left and formed Gauss Electrophysics with fellow employee Keith Johnson. Established in August of 1964, Gauss was to develop and market a like of high-speed audio tape recorders that could create duplicates much faster than anything else available commercially. These machines were a boon to the emerging audiocassette market, and Gauss found themselves with several highly lucrative contracts from most of the major players in the electronics business, including Capitol Records and Philips NV.

Two of the other principals at Gauss were Bill Cara and Tim Scott. Cara was Vice President and responsible for the marketing strategy of Gauss product. Tim Scott was a private investor who was also seeking support and funding for Gauss from other electronic manufacturers.

Partnership deals were explored with a number of firms who were purchasing tape replication equipment from Gauss - including Capitol Records, General Electric and NV Philips. Gauss was establishing an impressive name for itself in the audio industry and their proposal for a video disc system was tempting bait for any form wishing to get in on the bottom floor of the coming home video revolution.

In a 1967 move to obtain a partnership agreement with Philips, Gregg and Johnson made a complete technical disclosure to Jan L. Omes in hopes of obtaining funding for development of a consumer video disc. Philips declined, but despite their apparent disinterest to Gregg and Johnson, it would appear that it is from this point in time that Philips began development of an optical video disc system in their Eindhoven Laboratories.

When a partnership agreement with Capitol Records failed to materialize, Tim Scott went over to MCA to talk with his friend, Don Wynn. Wynn was a personal assistant to MCA's President, Lew Wasserman, on of the shrewdest businessmen to ever take on Tinsel Town. Wasserman, along with founder Jules Stein, had taken MCA from its humble beginnings as a talent agency and parlayed it into one of Hollywood's largest and most powerful producers of motion picture and television programming. Only the foolhardy messed with Lew Wasserman, the feeling in the entertainment industry being that there was God and directly behind him was Lew Wasserman. The audio side of Gauss was healthy and Lew Wasserman liked the idea of a consumer video product. He had 11,000 motion pictures gathering dust in the MCA film library and knew, if successful, video disc would give him another level of distribution for MCA products. Everyone agreed that an arrangement between Gauss and MCA would make a great marriage, and in February 1968, with a capitol investment of $300,000, MCA acquired 60 percent controlling interest in Gauss Electrophysics. Part of the collateral Gauss put up for MCA's investment was the patents Gregg and Johnson had already applied for to their audio tape replicators and video disc development.

It should also be mentioned here that MCA was not aware of the 1967 disclosure that Gauss made to Philips NV concerning video disc. MCA was aware that previous disclosures had been made but nobody had come through with funding for the project. As far as anybody knew, all rights still rested with Gauss. No one at Gauss or MCA even suspected that Philips was now running with optical disc in their Eindhoven Labs or were mindful of the patents issued to 3M concerning video disc.

As with 3M, conflict between Gregg and MCA was immediate. Once again, Gregg's personality did

not meld well with corporate politics. Shortly after the Gauss acquisition, MCA patent attorney Marvin Kleinberg

recommended that Wasserman hire an optical specialist from Hughes Corporation by the name of Kent D. Broadbent as

a consultant. The story told to me by more than one MCA executive was that Broadbent was hired to evaluate all of

MCA's holdings under their technology umbrella. This explanation sounds plausible until one realizes that the only

thing MCA was holding at the time of Broadbent's hiring was Gauss. It seems more likely that Broadbent was hired

specifically by MCA to evaluate Gauss, and more to the point, to take a closer look at what had been accomplished

by both Gregg and Johnson concerning video disc and report back to Wasserman.

On March 11, 1968, a disclosure titled "Technical Aspects Of the Consumer Videodisc Industry" was submitted by Gregg to MCA. Included in the document were contributions by both Keith Johnson and Kent Broadbent. The signatures of all three individuals are on the original document. The paper describes a method whereby a video master is produced using an electron beam as the mastering device and is played back on a home unit using fiber optics with a mercury arc lamp as a light source for transmission off of a replicated transmissive (non-reflective) disc. Subsequent patents were filed by both David Paul Gregg and Keith Johnson, and it is these late 1960's filings upon which rests Gregg's claim as the "Father of Optical Storage."

The relationship between Gregg and MCA deteriorated rapidly. MCA wanted a faster growth

rate for Gauss than the one Gregg was providing. There were problems with the high-speed tape replicators, and

his personality was, they felt, creating a logjam for the company. When Gregg pressed them for information

concerning MCA's plans for developing his video disc, talk become vague and was turned back to the problems with

the tape replicators.

At some point during all this turmoil, Kent Broadbent made his recommendations to Lew Wasserman concerning video disc. He told [Wasserman] the concept could work and that for the cost of what it took to make one motion picture (several million dollars), MCA could invest in the research and development of a system that would deliver them a way to duplicate and market their own video products (as well as own and license the format itself). Broadbent agreed to head the project and assembled a team of engineers for MCA with the understanding that he alone was to be in charge of the project and that it would all be done apart from Gauss and Gregg.

Three months after MCA's acquisition of Gauss, Gregg was forced to stop down as President and leave the company. In compensation for his departure he was paid $50,000 for his stock in Gauss along with a $400 a month stipend for three years, with the understanding that he would do no video disc research for any other interested parties. In 1969, Lew Wasserman convinced the board of directors of MCA to allocate funding for a new company entitled MCA Laboratories, a research division that would be devoted solely to the development of their proposed video disc system. It is from this point that we begin the DiscoVision® story and the advent of what we now know as contemporary optical storage systems.

MCA DiscoVision and the Torrance Labs

Laboratories for what was to be dubbed MCA Disco-Vision®

(the original, hyphenated spelling) were established at 1640 West 228th Street in nearby Torrance, California. The

distance from Universal City was intentional and involved just enough travel time to keep nosey MCA executives from

having the opportunity to just drop in at any time to see what was going on with what was dubbed by some as

"Wasserman's Folly".

The first person hired onto the DiscoVision Team was John Winslow, followed by James Elliot,

Ray Dakin, Dick Wilkinson, Manfred Jarsen, and Casaba Hunyar. This represents the first, original core of the

Torrance Labs. Later additions, and key members include Gary Slaten, Mitch Brown, Don Hayes, John Holmes, Carl

Eberly, Larry Canino and Ed Rubio. If these people are not the functioning fathers of the medium, they are certainly

the wet nurses who got the tiny infant to actually walk for MCA.

|

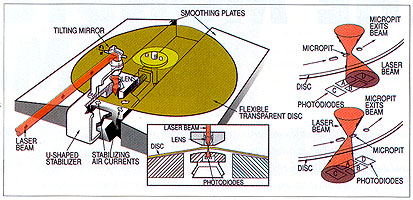

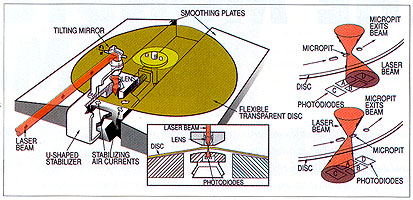

Optical Playback.

Spinning the flexible discs between U-shaped stabilizer eliminates the costly mechanisms to refocus the laser beam

when discs wobble. Air currents produce forces in the stabilizer that minimize vertical motion. TV signals are produced

and tracking occurs when passage of micropits through the fixed beam offset the beam's position on photodiodes beneath

the transparent disc. The area between micropits doesn't deflect the beam and no signal is created. The Beam axis tilts

across diodes C & D as the pits enter and exit the beam, generating the signal. Radial shifts in the track are detected

by diodes A & B, which are then adjusted for by the tilting mirror. |

The path Kent Broadbent and his team of engineers took in the development of the optical video

disc was far different from what David Paul Gregg's original papers and patents mapped out. After extensive interviews

with most of the original research team, I realized that very little, if anything, was said to them directly about Gauss,

Electrophysics' video disc research or David Paul Gregg's involvement with it. Certainly none of them were ever shown

the original disclosure presented to MCA by Gregg nor did they have any contact with Gauss, nor anyone from Gauss with

them. Keith Johnson, then President of Gauss, was invited to tour the Torrance Laboratories, but his input and/or advice

was never solicited concerning their endeavors. All the details anybody knew at the Torrance Labs were that MCA had

acquired some patents concerning the concept of a video disc and that Lew Wasserman was anxious to get something going

so that MCA could market their 11,000 motion pictures to the consumer market. Wasserman was to go on record as saying

that the realization of DiscoVision would be the crowing glory to his long career with MCA.

The first step in establishing a system was to select a light source for both mastering and

playback of replicated discs. Fiber optics, mercury arch lamps, electron beam mastering and clear transmissive discs

were judged impractical from the start and never seriously considered. It was felt that a reflective surface would

render the best images and the advent of the new gas laser beam provided the DiscoVision team with alight source suitable

for mastering and playback of video/audio information. A helium-cadmium laser was selected for mastering purposes,

and a helium-neon laser for playback of encoded material.

|

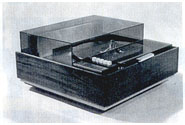

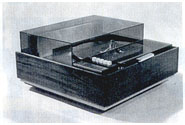

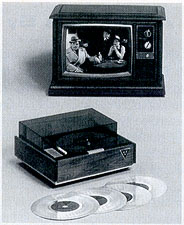

Numero Uno.

The DiscoVision FSX-101 was an early prototype player that actually worked and was used for the public demonstrations

by MCA in 1972. The arm at the back of the player swung out and read the disc from the outside in. Discs were floppy

and kept on track by the aid of an air bearing. |

Development proceeded in an orderly fashion, and by 1971 the core team at the Torrance Labs

were able to demonstrate the playback of a glass video master to the MCA executives. DiscoVision was no longer a

concept on paper, but a working reality. The team was working on a number of methods for disc replication, but all

felt that they were finally out of the woods. The first replicated discs were eventually floppy in nature and created

by a 2P Polymerization process. It was time to think about press releases and public demonstrations.

|

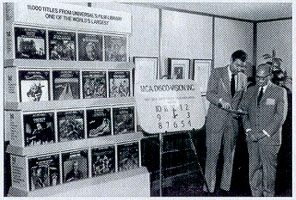

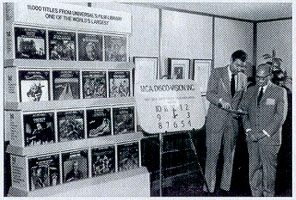

DiscoVision Debuts.

MCA DiscoVision President John Findlater and company prepares for the first public demonstrations at Universal City

on December 12, 1972. The press was ecstatic and hailed DiscoVision as "The film buff's salvation." |

On December 12, 1972, on a soundstage at Universal City California, MCA held the first in a

series of public demonstrations of their new DiscoVision system. After a short introductory speech by MCA DiscoVision

President John W. Findlater, the members of the press were shown a seven minute compilation of excepts from the MCA

film collection using MCA's laser based video system. The press was ecstatic. It had been hard for many to take MCA

seriously as a contender in the coming video wars. The purpose behind the public demonstrations was to not only blow

MCA's horn for what it had accomplished, but to also let everyone in the electronics community know that they and

DiscoVision were now something to be taken seriously.

MCA had gone to great pains to invite representatives from all the major electronics firms

from both the United States and abroad to their series of demonstrations. Despite the fact that the DiscoVision

system was MCA's baby, the simple fact was that they were not, in their own words, "a hardware company." The ideal

situation would be to license the system to a firm more savvy in electronics, and merely sit back and collect

licensing fees. As already noted, not everyone in the MCA hierarchy had been pleased by the decision to fund the

|

Own The Sting for the Same Price You'd

Pay to Take the Family to Go See It.

At the time that this press release was concocted, DiscoVision discs were to be single sided affairs that would

stack in trays and dropped down on the player like records. The single sided discs used in this photo were early

floppies that went by the wayside once Philips insisted on a rigid disc. |

Torrance Labs. The serious money had begun in 1969, and here it was 1972, with much still to be done before consumer

distribution could be implemented. The mood and tone for many in the company was that MCA should have stuck to what it

did best - making motion picture and television programs - not go off into an area that was totally behind their

normal expertise.

Philips NV and a "Period of Cooperation"

Among the guests at the press showings were the representatives from Philips of the Netherlands,

who were now giving private demonstrations in Eindhoven of their own laser based disc system. The two formats were

alarmingly similar, but MCA held the edge to their ability to demonstrate [from] a replicated disc. The Philips

demonstrations were from a glass master only. John Findlater had approached a number of American firms about becoming

involved with the production of DiscoVision and had even been to Europe and Japan in effort to solicit interest. The

American firms were cautions, and abroad he'd been met with an "MCA who?" tone of voice. Despite the demonstrations,

it was still hard for many of the established firms to take MCA seriously.

Both MCA and Philips had a great deal to loose if they were going to compete head on with each

other. TelDec (a joint venture with Decca of Britain and Telfünken of Germany) had a consumer unit that would

play back a ten-minute disc with a needle-in-groove system. The playback images were inferior to what MCA and Philips

had, and the supply of software to consumers was extremely limited - but it seemed to announce that the "Disc" was

coming of age.

The major consideration for both Philips and MCA was the knowledge that American electronics

giant RCA was committed to a system of their own dubbed SelectaVision. RCA's team had investigated numerous methods,

but had gone with a capacitance system that was based on a stylus/sled gliding over the surface of a molded plastic

disc. While the format made no allowances for some of the more sophisticated interactive features that LaserDiscs

provided, RCA assumed that the average family would be more interested in linear playback of materials than they were

in having the ability to run a movie backwards and forwards in slow motion. The SelectaVision discs, unlike their

laser counterparts, would also eventually wear out, but this phenomenon would only occur after 200 to 300 plays How

many times, PR people queried, would one family watch a movie anyway? Besides RCA's home units would be priced at

least a hundred dollars cheaper than DiscoVision's. Plus, they claimed, the SelectaVision units would be easier for

the consumer to maintain as most spare parts would be off the shelf items. Much of the press generated by RCA during

this time made MCA's laser technology sound expensive, complicated and the interactive features superfluous. MCA's

tact was to point out that lasers were not complicated at all and that the price difference between their system and

RCA's was minor considering that SelectaVision couldn't do much besides play back a disc that was going to wear out.

The boys in the marketing department at RCA were unmoved by MCA's counters. They were confident that the initials RCA

would carry much more weight with the public than MCA.

In September of 1974, after a great deal of corporate haggling, MCA and Philips finally signed

documents that signaled the beginning of what was termed a "Period of Cooperation" between the two companies. Both

laboratories would freely exchange information, standardize the format, and then create a joint licensing office for

their optical disc products. MCA and Philips both needed another competitor like they needed holes in their heads -

there were too many incompatible disc formats being proposed already. It made fiscal sense to pool their efforts and

|

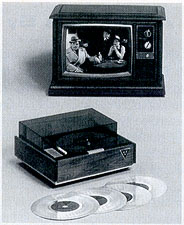

Magnavision in the Home.

A pre-release press photo from the folks at Magnavox demonstrates just how easy it is, even for the kids, to

operate LaserDisc. |

head into the market together.

Despite the cordial working relationship between the Torrance and Eindhoven Labs, corporate

dealings continued to be anything but. Relations were, at best, tense, with hostilities reaching a fever pitch, when

after standardization had been arrived at by both labs, Philips tried to file international patents that would

effectively give them total control of the process. After heated arguments and with the reality of long and costly

lawsuits looming on the horizon, tempers were cooled and the pie divided up so that both Philips and MCA would share

equally in royalties incurred from all licensing fees. It was agreed that Philips would be responsible for

manufacturing and distributing hardware for the consumer market through the newly acquired Magnavox network, while

MCA would manufacture and distribute software programming through their DiscoVision subsidiary. However, the profits

from each of these areas would not be pooled. MCA would keep their profits from DiscoVision consumer purchases, while

Philips would reap what they could from machine sales. It was also agreed that Philips was free to develop and license

the European markets, while MCA would confine their consumer efforts to the United States.

With open hostilities over, it appeared that both MCA and Philips could now turn their

attention to the manufacturing and marketing of the DiscoVision format without further interruptions. The only flaw

in this arrangement, however, was the United States Justice Department's Antitrust Division.

USA vs MCA / Philips NV - MCA vs Sony

Anyone interested in becoming familiar with the more questionable side of MCA as a corporation

should read Dan E. Moldea's lengthy testament against them entitled "Dark Victory: Ronald Reagan, MCA and the Mob" (1986,

Viking Press). Known affectionately to some as "The Octopus" for its aggressive and all encompassing business tactics,

MCA had a long and well documented history of acquiring complete control of every phase of whatever venture they

become involved with. The government kept close eye on MCA's activities, and this was not the first time

the Justice Department had investigated them on antitrust charges. To own the rights to the hardware, software,

and replication process for an entire video system fit quite nicely into the MCA philosophy, and in August of 1975,

recommendations were made within the Department of Justice concerning formal charges to be filed against MCA and

Philips for violations against the Sherman Antitrust Act. In characteristic fashion, MCA chose to ignore much of

the Brouhaha, leaving Philips to meet with the Antitrust Division to answer allegations that their joint licensing

agreement would put a stranglehold on the disc industry.

The response from Philips was that if the Justice Department put a stop to DiscoVision, they

would end up putting RCA in the marketing position that they were accusing MCA and Philips of trying to gain.

Ultimately, the only thing generated was a great deal of paper work. The investigation continued during the

development stages of DiscoVision and, eventually, even RCA and their system were brought into question as well.

But the Justice Department finally ran out steam in pursuing the matter. The relatively poor showing of both formats

in the market place made the issue one of small potatoes, and the fact that any company could get their product

onto video disc if they so wished made the antitrust charge a moot point. The case is only an interesting wrinkle

in the fabric of the DiscoVision story, but does serve as an example of the Justice Department's feelings toward MCA.

So, while insiders speculated as to which disc format would hit the consumer market first

(and ultimately prevail), Sony of Japan was planning a little video revolution of its own. The main line of attack

was to appear on American stores in the form of a home videocassette recorder called The Betamax.

In September of 1976, Sid Sheinberg, now the Acting President for MCA and Universal Pictures,

was asked to give his approval for the use of the names "Kojack" and "Columbo" for a print ad that was to promote the

time-shifting capabilities of the new Betamax machines ("Now You Don't Have To Miss Kojack Because You're Watching

Columbo...or vice versa"). It was anybody's guess at this point what the legalities would be concerning copyright

infringement and home video recording. Was it legal to record off the airwaves, or wasn't it? Sheinberg and

Wasserman felt MCA had a perfect case to make against the advent of home recorders and a week later the fateful

"Kojack/Columbo" letter, the two paid a call on Sony in New York to let them know of an impending suit.

.jpg) |

Industrial Strength Laser.

The DiscoVision PR-7820 Industrial Player was the first laser player manufactured by Pioneer and the only optical

disc machine to be built according to the specifications laid out by the original DiscoVision team. The laser was

stationary and mounted above the disc, the disc then slid into the unit and slowly moved out as the information was read. |

Oddly enough, MCA was initially interested in Sony as a possible manufacturer for their

disc players. Sony was interested and envisioned tape and disc coexisting side by side the way LPs and audio

tape already did, but MCA saw videotape as a foe, not friend, to DiscoVision. It viewed the Betamax as a

multifaced monster that would gobble up copyrighted programming and cheat producers out of the millions coming

to them in royalty fees. MCA knew this technological beast had to be stopped at all cost, and gladly took on

the mantle of St. George to Sony's Betamax dragon. On November 11, 1976, the opening volley was fired in the

landmark "Sony/Betamax Case" with MCA filing papers in Los Angeles Superior Court against Sony. Despite backing

from both Disney and Warner Bros., plus the implied moral support of the entire motion picture industry, it was

a suit MCA would eventually lose - along with their high hopes for DiscoVision in every home.

Sony's interest in disc continued and in September of 1979, they agreed to exchange

patents with Philips NV. By 1980 they were producing industrial machines and pressing discs. Their product was

highly regarded in the field and they eventually won the contract to supply industrial machines to the Ford Motor

Company, much to DiscoVision's annoyance.

Heading For the Starting Gate - Enter Pioneer

Despite the corporate animosity between MCA and Philips, the push was on to get DiscoVision onto

the market before it was totally eclipsed by the advent of the VCR. Although MCA and Philips had agreed to standardize

and support each other in the consumer marketplace, there were no legal ties binding them other than the joint licensing

offices. MCA was certainly on the lookout for other electronics firms to include in their venture, and when Philips

declined any interest in investigating industrial applications of the format, MCA had an open door to let other members

of the electronics community come on board without ruffling Philips' feathers.

The early 1970's knew Pioneer of Japan primarily for their home and car stereo systems. The

Japanese heavyweights at this point were Sony, Matsushita and JVC. These were the big boys of the blossoming Home Video

Market, all pushing the videocassette and preoccupied with their own in-fighting concerning standardization (Beta vs VHS).

Pioneer was a comparative lightweight in the field, not involved or committed to videocassette and certainly not looking

to become a handmaiden for the VCR. They were, however, very interested in getting in on a video system they could call

their own. The invitation to join forces with MCA on industrial machines for the disc market gave Pioneer a foot in the

|

Finger Tip Control on DiscoVision.

The massive remote control unit for the PR-7820 Industrial Player. Believe it or not, the design is still pretty

much the same for today's industrial players. |

door they desired on an alternative format. It also gave MCA more support for DiscoVision, as well as someone to fall

back on should relations with Philips become to strained or collapse altogether. In October 1977, the Universal Pioneer

Corporation (UPC) was formed amid much fanfare, and Pioneer took the first step on a road that would eventually leave

them with almost total control of the consumer market as well as the contents of the DiscoVision patent package.

As soon as Pioneer become involved, the engineers over in the Torrance Labs were instructed to

start funneling off technical information to Japan so that Pioneer could begin work on the new industrial machine, the

PR-7820. The original understanding was that Pioneer would manufacture machines only, and software would remain the

sold domain of MCA. Eventually though, Pioneer deduced that if they were going anywhere with product development,

they would need to have hardware and software capabilities in Japan. In a series of tense meetings between

Pioneer and MCA, Lew Wasserman finally agreed to let Pioneer produce software, much against his initial wishes. The

scuttlebutt to Wasserman was that it would only be a matter of time before their industrious Japanese partners found

a way to go around the DiscoVision patents and that it was better to keep thins in the family rather than create unrest.

Meanwhile, as MCA frantically pushed ahead with disc manufacturing, Philips was hurriedly

assembling consumer players in Eindhoven. One of the major reasons for the acquisition of the American firm Magnavox

by Philips was for the manufacturing and servicing of the new optical disc players. However, the assembly plant in

Knoxville, Tennessee was not yet up and running, so the first consumer machines had to be fabricated in Europe and

then air freighted to the United States.

And They're Off - DiscoVision Debuts

On December 13, 1978 representatives from MCA DiscoVision and the Magnavox Consumers Electronics

Company held a joint press conference in the ballroom of the Regency Hotel in New York City. This was the big kick-off to

celebrate the first commercial sale of discs and machines that was to take place in Atlanta, Georgia two days later on the

fifteenth. It was nine years and God knows how many millions of dollars since Kent Broadbent and his small band of

engineers started the project in 1969. There had been numerous press showings and demonstrations since MCA's first

announcement of the format, but now DiscoVision/Magnavision was to be cast forth into the consumer market to sink or

swim on its own. The hope was that consumer loyalty would develop quickly so that LaserDisc could establish a hold

next to the VCR and - more importantly - take a lead against the coming RCA CED disc format. Most of the other major

electronic companies had backed off on their respective disc systems, only RCA forged full steam ahead with theirs. If

MCA and Philips were to be in the dominant position with video disc they would have to move quickly and decisively.

Sales were brisk in Atlanta, with machines and discs selling out in a matter of hours. Too bad

all the ballyhoo ended up being for naught. Depending on who you talk to, some people will say that the system was

|

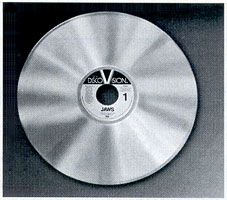

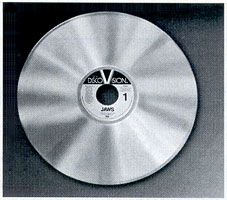

JAWS Only Available on DiscoVision.

This Spielberg blockbuster was the first DiscoVision title to be mastered in complete form and was one of the main

titles meant to push vacillating consumers towards LaserDisc as a medium of choice. For many the bait worked. |

released either too soon or too late. Whatever the reality, MCA was painfully aware that it had to get something on

the market, and soon, or be washed away in a wave of videocassettes. Judging by dates stamped into pilot disc runs

I was able to obtain, serious mastering of the DiscoVision library began in the Torrance Labs in 1977. Early press

releases announced the DiscoVision library, forever point to the 11,000 films in reserve in the MCA archives. In the

November 25, 1975 issue of the Hollywood Reporter, John Findlater is quoted as saying that the opening selection

of titles would be around 500. By April of 1977, the public relations people were informing anxious consumers that

there would be at least 300 titles to choose from. By the time Norman E. Glenn, the MCA Vice President in charge of

orchestrating the DiscoVision Catalog, had reconciled fact with fantasy, the list had been whittled down to just over

200 titles. Of the 113 entertainment titles originally announced, only 81 were to ever see the light of day, with

many titles released in batches so small or with defect rates so high that only a few dedicated consumers were ever

able to track down playable copies. In fact, out of the 200-plus selections in the opening catalog there were only

some 50 titles to choose from at the Atlanta and Seattle openings. This lack of software to support the system was

a chronic problem for dealers, and was considered by many to be the reason for LaserDisc's near death experience in

the late seventies and early eighties. Distributors handling DiscoVision in the beginning said they were lucky to

have 20 different titles at a time, and had a difficult time pacifying angry consumers who had purchased hardware

based on the promise of dozens of new releases every month.

Suffice to say, whatever glory there was to be enjoyed from the debut was fleeting. One store

owner even expressed disbelief to me that a class action suite was never brought against MCA and Magnavox for a product

that appeared, to the average buyer, to be far from ready for public consumption.

Government Interest and IBM

With a possible 54,000 still frames per CAV side, optical discs are still the densest form of

|

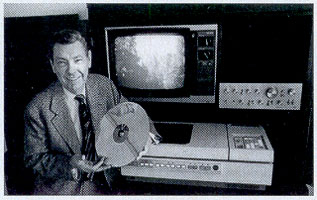

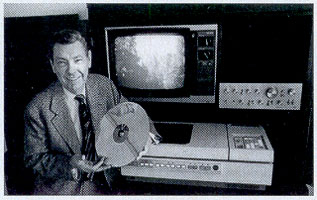

And the Discs Never Wear Out.

John Findlater and the Pioneer-built industrial player that was the first step in that companies journey to complete

dominance of the optical market. |

storage around - a point certainly not lost on the United States Government. Certain U.S. agencies had been in

contact with MCA concerning possible use of the medium within the government. At this time, MCA was aggressively

looking to market DiscoVision in connection with point of sale and in-house instruction basis for large corporations.

Long before the Carson disc pressing plant was even up and operational, the sales force at MCA had managed to sell

General Motors on the idea of installing Video Centers in roughly ten thousand of their agencies - centers where

consumers could watch a video overview of the new lines and a place where dealership employees could keep up with

the latest developments in the company. Despite all this activity, there was still lingering doubt in many people's

minds as to whether MCA, as an entertainment company, could really pull off a concept so deeply rooted in technology.

Something was needed to make the whole thing gel, a touch of authenticity, something to make the whole thing legitimate.

That legitimacy arrived in the form of a partnership struck between MCA and IBM - one of America's largest and most

formidable electronics experts.

Early negotiations between MCA and IBM were kept strictly hush hush. Very few within either of the respective camps were aware that anything was up, and knowledge of the talks become common only after terms had been finalized between the to company heads. IBM had committed much time and effort to their Castle Project, a research wing dedicated to developing IBM's own optical storage system. Years of research and millions of dollars had netted them practically noting in terms of actual product, and they arrived at the bargaining table with nothing more than a desire to get in on what MCA had developed. In September 1979, the two companies formed a joint venture called DiscoVision Associates (DVA). IBM received 50 percent interest and MCA received the opportunity to, as one MCA executive put it, "go through 50 million dollars of IBM's money like shit through a goose."

One of the more bizarre incidents at this point was the disappearance of Kent Broadbent from the scene. Apparently, the ink was barely dry on the MCA/IBM deal when Broadbent suddenly, and without any explanation to his employers and fellow workers, left the company, put his house up for sale and moved his family lock, stock and barrel to Utah. The lucrative contract he had obtained from MCA to head up the project provided him with financial freedom for the rest of his life, and Broadbent remained incommunicado concerning his participation with MCA DiscoVision for the remainder of his life.

Before his death, I asked Broadbent why he left so quickly once the IBM deal was finalized. He claimed that his move was neither sudden nor unexplained. His story was that he felt he had accomplished the task that Lew Wasserman had set before him and that he simply wanted to move onto other things. If he did disclose his plans to Lew Wasserman, nobody else was told, not even DiscoVision President Jim Fiedler, who eventually took a drive out to Broadbent's Southern California residence to conform that the family was indeed no longer there. An odd, and rather confounding way for Broadbent to end his association with MCA and the DiscoVision project.

In February 1980, MCA transferred its shares from Universal Pioneer Corporation into DiscoVision Associates, making IBM a 25 percent holder of that company as well. The rest of the makeup of UPC went 50 percent Pioneer and 25 percent MCA.

Primarily, the IBMers were now handling the bulk of the day-to-day running of the Carson plant and further plans for expansion of DVA. It was MCA's hope that, given their past track record in the electronics field, IBM would eliminate the problems with quality control and low yields at the Carson plant and put disc production into high speed.

Just prior to the IBM merger, engineers from the Torrance Labs were instructed to spend time

at the Carson plant in an effort to clean up production problems and improve disc yields. To the original band of

engineers, the problems MCA was experiencing with full scale disc productions were neither complicated nor mysterious.

From the gate, there had been a great divide between what the engineering team felt was required and what executives at MCA

wanted to hear. The folks in The Tower of Power (the affectionate name used for MCA headquarters on the lot in Universal

City, California) felt that the recommendations by the engineers in Torrance were excessive in terms of both time and

money. MCA had to move quickly to make deadlines and they didn't want to go broke in the process. George Jones, an

executive in charge of MCA's Decca Records division, was called in and instructed to get the Carson plant up and

running on time and on budget.

Jones, a dedicated and conscientious executive, was dismayed to discover that, despite what Wasserman had been told by his engineers, DiscoVision was anything but ready for mass production. Shown crisp, clean stampings as examples of DiscoVision's readiness, Wasserman had not been informed that he was looking at the best disc culled hundreds of pressings.

Still the release date for DiscoVision/Magnavision had been announced and come hell or high water, there would be a rollout in Atlanta in December.

The space obtained in Carson for the DiscoVision pressing plant had housed a furniture manufacturing firm. Despite a thorough house cleaning, it was impossible to rid the site of all sawdust particles. The plant grew in a House that Jack Built manner with plastic hoods being dropped over pressing equipment in an effort to have some sort of clean room status.

MCA figured that the cost per side on a disc was about $1.25. This included materials, labor and packaging. A stamper was good for about 10,000 pressings before it needed to be replaced. However, with the average yield of playable discs running at less than 10 percent per run, MCA was actually loosing money on their investment right from the gate.

Horror stories concerning the day-to-day operation of the Carson plant are numerous and - in some cases - almost beyond belief. There appears to have been no consistent maintenance of a clean room status and employee sabotage (conscious or unconscious), especially after IBM entered the picture, was a common occurrence. Adding fuel to the fire were the quality control problems nobody could have foreseen. Raw materials required for mass replication varied from batch to batch. Some appeared stable for a time and would then suddenly start attacking the discs weeks after replication. The analogy of video discs being only a small step up from phonographic records was a line used over and over again in early DiscoVision press releases and many MCA executives believed disc production would pose few problems. It was hard for them to understand why, after years of success with Decca Records, was DiscoVision experiencing such massive problems? It took a great deal of time to realize that the scope of disc production went far beyond anything MCA had encountered before. It wasn't the easy-as-pie, pennies-a-glass system everyone hoped it would be. DiscoVision quickly turned from a crowning MCA glory into a major corporate headache.

The Beginning of the End

The first order of business for the newly formed DiscoVision Associates was the outfitting of

corporate headquarters. After all, the merging of America's largest producer of motion pictures with America's most

prestigious producer of electronic equipment was a Big Deal. DiscoVision Associates needed offices that would impress

and proclaim their importance to the world. The new corporate offices, assembled in an impressive new building MCA

had acquired in Costa Mesa, California certainly radiated that importance. Impeccably furnished, handsomely outfitted

and with its own experimental pilot disc pressing facilities for small, rush orders, it was truly a wonder to behold.

Unfortunately, how this translated to those on the firing lines of production was that the new

suits were more interested in picking out the right paintings and desks for Costa Mesa than they were in cleaning up

the Carson plant. Plans and property for a new plant had been acquired before the formation of DVA. Utilizing all

the knowledge that had been garnered from the initial production runs, DiscoVision engineers wanted to see the new

pressing facility up and running so that they could close down Carson, gut it, and rebuild it along new guidelines.

After the company reorganized, DVA executives were loath to the idea of any down time in consumer disc production.

Defective or not, there was not enough software on the market to support the hardware as it was. Both Pioneer and

Magnavox were doing extensive campaigns in order to sell machines, and much of the stress was on the size and scope

of the disc library available to consumers. The simple fact was that there was very little for consumers to pick

from, and in some instances PR was included that pointed out applications that could be handled by disc

(bilingual language lessons for instance), but for which no software existed.

Slowly it began to dawn on those working at Carson that very little time and effort was going to be

thrown in their direction. The thrust for DiscoVision Associates was on the future, not on the past. The Carson plant

represented a shaky beginning for the optical disc, and the formation of DiscoVision Associates was the harbinger of a

bright and shiny future. To those keeping track of funding and focus, it became obvious that for DVA the future lay in

Japan. To many at the Carson facility it appeared that they were being pushed aside so that Pioneer could be courted

properly. Accordingly, engineer Gary Slaten was instructed to document the entire operation of disc manufacturing and

|

But I Just Want to Return the Disc.

Returning defectives required a lot of paper work for early customers. MCA wasn't trying to make things

difficult, they were just trying to get a bead on what was causing a horrendous defect rate. Sets that left

the plant in good shape often arrived at stores already rotten. |

deliver the resulting papers over to Pioneer. This enabled Pioneer to begin planning and construction of their proposed

disc pressing plant in Kofu, Japan. Visiting engineers from Japan were given Carté Blanché of the Carson

plant, where they were allowed to photograph all phases of production and ask whatever questions they felt still needed

to be answered in order for them to roll into full disc production.

Number One Son

Pioneer in Japan made great strides in perfecting what had come before them. The industrial machines

were performing well and their first consumer machine, the VP-1000, was selling for less money that Magnavox's and with a

remote control (something Magnavision lacked), it was giving the potential customer more bang for the buck. It was

certainly more reliable and produced what many considered a superior image. The disc pressing plant in Kofu was up and

running by October 1980, and had been constructed on a totally clean room basis, with many of the pressing processes

automated. To any consumer buying discs, this meant that a Printed in Japan legend on the bottom of a jacket was

your assurance that the disc you were holding would play and be [relatively] speckle free. Anything still coming out of

the Carson plant was still a crap-shoot and would most likely have to be returned several times before an acceptable copy

was obtained. Even then, acceptable usually meant defects a disc buyer could tolerate. Certainly there were defects

from Japan, but not on the overwhelming numbers from the disc runs still being generated in the United States. Entire

runs were still coming out bad, making the tension at the Carson plant even more unbearable. Pioneer was the good son

to DiscoVision Associates, while the Carson plant was quickly becoming the black sheep of the family.

It was a simple matter of economics. It would take DiscoVision Associates much time and many

millions of dollars to bring the U.S. facilities up to the quality of what was being done in Kofu, and with disc sales

taking a nose dive in the consumer market, it seemed more like throwing good money after bad.

The Kiss of Death

DiscoVision Associates was MCA's last chance for the project to become the "Jewel in the Crown" that Lew Wasserman envisioned. For all their posturing in the marketplace, the simple fact was that the optical disc had not caught on with the American public. VCR's had taken the lead and the only people faithful to LaserDisc were those video purists who could appreciate the jump in quality that discs could offer. The simple fact was that the average household wanted something that had the ability to record and playback. Most budgets could not afford the expense of videotape and disc, and so disc went by the wayside for economic reasons, if nothing else. Insiders in the industry first thought it was logical that the American public would be interested in building a video library in the same way they collected books. The reality was that people were more interested in renting and returning a movie than they were in owning it. Certain classic titles always had the appeal and possibility of repeated playing, but most consumers realized they were only interested in seeing a title once or twice. That certainly didn't justify a purchase.

Also, studies today show that the average person watching prerecorded video programming is still only interested in being able to watch it without any technical distractions. That is to say, that as long as the tape is free from distortions (i.e., rolling lines, snow, fuzzy audio), the average consumer is just as happy with tape as they would be with disc.

Another nail in the coffin was the failure of the RCA CED disc system. Despite the affordability of machines and the glut of programming available for the system, RCA was unable to interest enough of the American public to make the whole thing profitable. When the CED disc sank without a trace, the man on the street who knew very little about disc, let alone the difference between the two systems, assumed that if a company as large as RCA couldn't get the format to fly, then video discs in general were a thing of the past and doomed to extinction.

Between the funding from both MCA and IBM, the amount of monies available to the administrative staff of DiscoVision Associates had been considerable. It was MCA's understanding that IBM's $50 million would be the last major capital investment needed to keep the company afloat, and that DiscoVision Associates would now start generating enough business to keep it alive. By the beginning of 1981 however, the powers that be running DiscoVision Associates were back begging to the boards of both IBM and MCA, claiming that the cupboards were bare and that additional funding was going to be needed.

There are various versions of the who wanted out of disc replication first story. One is that MCA was finally at the end of its rope with DiscoVision. It had been funding the project since 1969 and here they were twelve years later, fighting an uphill battle against the VCR, still with manufacturing problems galore and now added millions were going to be needed to keep it going. More than that, Lew Wasserman's "Crowning Glory" had become a corporate embarrassment. Despite years of commitment to the format, Sid Sheinberg and Lew Wasserman finally felt it was time to throw in the towel and declare DiscoVision a loser in the video wars. Although they technically never lost money on DiscoVision, it made more sense to cut their losses and move on to bigger and better things. Their loss in the Sony Betamax case only highlighted the issue and certainly seemed to harbinger the demise of video disc.

Another version has IBM as the heavy, the theory being that IBM had obtained what they wanted (working knowledge of the format and partnership on the patents) and that they were no longer interested in dabbling in the consumer marketplace. What use they could make of LaserDisc would be done so in industrial applications, an area where they had much more expertise. Besides, no matter what happened, they would always share in whatever licensing fees were generated by the patents. DiscoVision Associates, as a disc replication entity, had provided slim pickings for a company the size of IBM. They too felt the consumer market was doomed for disc and thought it was time to get out while the getting was good.

Whatever the truth, by the middle of 1981, the staff at the Carson plant had been cut to the bone and disc production slowed down. The last DiscoVision catalog dated July 1981 had but a scant 35 titles for sale, with a number of them being pressed at the Kofu plant in Japan. The handwriting was definitely on the wall.

Talks proceeded smoothly between DiscoVision Associates and Pioneer for the sale of the Carson facility. MCA and IBM wanted out, and Pioneer would finally have full responsibility for doing what they could with LaserDisc. A strong market for the format had developed in Japan, a country where consumers must purchase, not rent their software. The economics in a Purchase Only market are plain. Not only does LaserDisc produce a superior picture, but it's also cheaper to produce. Video disc had a side-by-side relationship with the VCR almost immediately in Japan. For Pioneer, who had invested practically nothing in formulating the actual invention, the odds were stacked in their favor that they could establish a beachhead in the consumer market. They could afford to bide their time and wait.

In February 1982, the announcement was made that the sale of the Carson plant was eminent and that both IBM and MCA would no longer be in the business of manufacturing LaserDiscs. The sale was finalized in March 1982. Although it was rumored that Pioneer had been given a "sweetheart deal," the sale of the Carson plant had been lucrative, as Sid Sheinberg had said to the press concerning the matter: "Bargain basement you don't get from MCA." (in truth, MCA was to sell DiscoVision three times - once to IBM, once to Pioneer to form Universal Pioneer Corporation and, finally, when Pioneer purchased DVA.) The impressive corporate building in Costa Mesa was eventually sold and the staff needed to administer and maintain licensing moved to more modest quarters, also in Costa Mesa. All that remained of DiscoVision Associates were the highly valuable patents, to which IBM and MCA maintained 50/50 ownership. At least if Pioneer eventually did establish a market, IBM and MCA would share in the profits, and with the audio Compact Disc on the way, the two stood to make more money thorough licensing and royalties than they did through manufacturing. (Eventually even the patents were to pass onto Pioneer. IBM and MCA sold DVA to Pioneer in 1989 for a disclosed purchase price of $200 million dollars.)

The Question of Authorship

In 1991, I began my investigations based on one simple question. Who invented the medium of optical storage? The history of the telephone, television, the automobile and hundreds of other modern conveniences is fairly well documented. However, the question of authorship on optical storage has been obscured, manipulated and in some instances, purposely buried from the public eye. The average consumer probably believes that Pioneer invented the LaserDisc, Sony or Philips the CD and God only knows where they think DVD came from.

For many years, David Paul Gregg has declared long and loud that he is the sole inventor of the optical disc. A mighty large claim and, until comparatively recently, a claim largely laughed off by most people working directly in the industry.

Throughout the 70's and 80's, DiscoVision and MCA pooh-poohed David Paul Gregg's claims as pure nonsense and declared that his original findings were unworkable and in no way reflected in the system that was ultimately arrived at. They would point to his patents and claim that they did not in any way demonstrate the medium as it was finally arrived at. Gregg called for electron beam mastering, DiscoVision went with Lasers. Gregg advocated a transmissive disc, while the DiscoVision disc was reflective. Outside of pits and lights, they would say, there was nothing to suggest the format ultimately devised by MCA DiscoVision and Philips. To them, calling David Paul Gregg "The Father of Videodisc" made as much sense as calling H.G. Wells the creator of the NASA program. An aesthetic connection, they said, could be made, but certainly not a practical one.

Why then is DiscoVision Associates/Pioneer suddenly parading Gregg around as "The Daddy of the Disc?" Because attached to the question of authorship is the issue of ownership and he who owns the relative patents concerning optical storage will have the world, literally, on a "Silver Platter." The motivation for corporations to spin control and rewrite the history of optical storage is quite simple - royalties.

When Pioneer paid $200 million to acquire DiscoVision Associates, they bought primary control over all CD and LD production. For many years Philips used and licensed disc technology without paying any royalties to DVA, claiming their patents exempted them from any obligation. DVA eventually brought suit against Philips, and ultimately won an out of court settlement from them in 1988. Philips and their licensees now pay DVA along with everyone else. In the early 1970's, 3M even brought suit against Pioneer, DiscoVision Associates and MCA and ultimately received a settlement in their favor based on their 1962 prototype player and discs.

But ownership of any technology comes to an end when the relevant patents connected with it lapse seventeen years from date if issue (not the date of filing). The original 3M patents are no longer in force and many of the key DVA patents have already lapsed and many will loose their steam by the turn of the century.

Now we have entered the area of DVD and once the average consumer has the ability to record and reproduce video and audio optically in the privacy of their own home, silver discs will replace magnetic storage than CDs replaced turntables and vinyl discs. All those cassettes in your collection will either be in the trash or down at the Goodwill for a nickel each. For now anyway, the future appears to be in optical storage.

At the center of the Gregg controversy is paten Number 4,893,297 issued to DiscoVision Associates on January 9, 1990 but originally filed by David Paul Gregg on June 6, 1968.

For almost two decades, this Gregg patent concerning an embossing method of producing discs was thought to have been lost or rejected by the U.S. Patent Office. However, this early video disc patent was resurrected by Ron Clark, DVA's patent attorney, shortly after the acquisition by Pioneer, re-filed and ultimately issued to DiscoVision Associates with Gregg named as the sole inventor. Within DVA, this patent is referred to as "The Silver Bullet." It is upon this patent which rests DVA's claim to preeminence in licensing and David Paul Gregg's claim to sole authorship.

What makes patent Number 4,893,297 key are the seventeen claims listed therein. The method of disc producing does not resemble industry technology. The fact that it does not isn't important. What is really being patented here is a disc-shaped object with an irregular surface which has audio/video information encoded on it, which is then read back by a light source. You can't get much broader than that. It would be like having a patent on the wheel. Anyone that used a circular object that resembled your wheel would have to pay you a licensing fee in order to use it.

The part that's interesting is that every time a patent is re-filed, the claims contained in it can be amended to reflect technology that may not have existed as the time of the original filing. In other words, if your patent on the wheel were pending and someone came up with a wheel with spokes, you could abandon the original, amend it and re-file so that it would now encompass any deviations on the original design. The last filing date for this original 1968 patent is actually March 8, 1989. The claims listed are so broad and general that it would cover any optical storage medium that required a round disc, pits of information and a light source to read it back. This means that this early patent would not only give DVA/Pioneer extended life over licensing after the more specific DVA patents had lapsed, but if left unchallenged, would give them licensing rights for any kind of audio or video disc production, even if the method of production were different from the current standards. Hence the name, Silver Bullet. It would effectively shoot down any wayward manufacturer trying to avoid paying licensing fees by going around the more technical DVA patents. After years of decrying David Paul Greg as "The Father of LaserDisc," it suddenly becomes fiscally beneficial for DVA to officially establish Gregg as the sole source of optical storage by using the same documents used to defame him in the past.

In the past years, a number of CD and LD manufacturers have been questioning DVA's right to all these royalties and more recently have begun to question the validity of Gregg patent Number 4,893,297.

How is it, you may ask, that a patent thought to have been rejected by the patent office in 1968 suddenly reappears and is issued in 1990, some 22 years later?

The story, truly worthy of Lewis Carroll is as follows:

Sometime before Pioneer's buyout of DiscoVision Associates, some painters working in the U.S. Patent Office discovered a box of patents in the ceiling of an office they were working in. It seems that the clerk in charge of these patents had the odd habit of hiding patents he was dealing with for reasons yet to be explained (too difficult to attend to, perhaps?).

And so, this early lost Gregg patent magically reappears shortly before Pioneer takes over the DVA patent package and is issued shortly thereafter, miraculously giving them extended life on licensing and the attendant royalties.

What a coincidence!

To add fuel to the fire is the fact that David Paul Gregg has been retained by DiscoVision Associates as a consultant, pulling down a tidy yearly sum from the very company that dismissed him as a crackpot. One would like to think of it as some sort of poetic justice, but the reality is that DVA needs Gregg in their camp lest he be available to any competitor questioning the validity of Pioneer's Silver Bullet.

So now we know why David Paul Gregg is suddenly being feted as "The Father of Optical Storage."

But what is the reality?

For years, I have alternately tried to prove and disprove Gregg's claim to the title. The simple fact is this - "from an aesthetic standpoint" it is impossible to find anything that predates Gregg, concerning an optically read video disc. Any experiments concerning optical video disc before David Paul Gregg came along concerned themselves with either contact systems not unlike the RCA CED format (Baird) or a process that revolved recording video information as whole images in microform (Toulon). In a 1991 interview with Gregg's partner, Keith Johnson, still a highly respected engineer in the audio/video field, he had this to say about Gregg's authorship: "Even though his (Gregg's) method might not be what we use today and probably might not have even worked, there is no question that he was on the right track and that he saw the critical key pieces that would fit and make the system work."

Go to the heart of Mincom's desire to develop optical storage, Philips' and MCA's investigations into the medium, and you will find the name David Paul Gregg under the pile of corporate rubble. Philips and 3M both had dealings with Gregg and there is little doubt that MCA's interest and subsequent funding of DiscoVision was a direct outgrowth of their involvement with Gauss Electrophysics.

It is my personal opinion that the practical birth of modern optical storage began in the tiny labs of 3M/Mincom in Camarillo, California. The 3M patents predate anything by Gauss, Philips or DiscoVision and they did produce a prototype that optically read a disc long before Kent Broadbent ever hired the first members of the Torrance Labs.

Would 3M have had a video disc effort without David Paul Gregg? Probably not. At least, not in the time period at which it developed. Contemporaries of Gregg from 3M are reluctant to give him much, if any, credit for the concept. Interestingly enough, most of his detractors from 3M never actually worked on Project D. Known primarily as an idea man, it is their feeling that Gregg would never have gotten the video disc off the ground without the help and his personality problems precluded him from ever being a part of a working team of engineers. They are also quick to point out that similar concepts were being bandied about in the labs and that parenthood of the video disc concept couldn't possibly be assigned to any one person.

Despite this, in all of my years research, I have been unable to unearth one concrete bit of evidence that contradicts Gregg's claim that he is the genesis of the optical disc project at Mincom. If anything, there are those still alive and close enough to the project, with no love for David Paul Gregg, who admit never having heard of such a thing in the labs until his arrival at 3M/Mincom.

So David Paul Gregg becomes the source. Who are the people responsible for getting it off the ground?

Certainly the original band of engineers assembled by Kent Broadbent deserve some long delayed credit. Never have I met a group of individuals so quick to recognize others for their contributions, or so delighted to give credit where credit was due. All parties concerned were genuinely pleased to have been part of the process and were delighted that their baby had survived its rocky infancy. It was MCA, not Philips, that first transmitted images from a replicated disc.

In spite of any of the stones that could be thrown at Lew Wasserman and MCA, it is doubtful that the optical video disc would have gotten anywhere without the studio's infusion of millions of dollars into the format and the availability of their overwhelming film library. Certainly Philips would have had major problems amassing a catalog on their own, and one of the primary reasons for 3M's abandonment of Project D in the late 1960's was the problems attendant to the acquisition of a software library.

And Pioneer? Where is their true place in the history of optical storage? Well, Pioneer ended up doing with the Japanese do best. They took a scrappy new technology, streamlined it and made it more cost effective. Without Pioneer, it is likely the optical disc would have gone the way of RCA's CED format. Surely some sort of optical storage system would have survived for medical and industrial purposes, but the consumer market would have certainly dried up without their support. Pioneer does not deserve credit for creating the format, but they certainly must be credited for quietly perfecting the system and providing life support to the patient when its original parents had abandoned it for dead. For that they deserve the undying gratitude of consumers happily playing CDs, LDs and DVDs.

The indirect lifesaver for the optical video disc turned out to be the audio CD. It provided the mass consumer education that was needed to entice the public into considering laser as the system of choice. Buyers were immediately impressed by the quantum leap in quality that CD sound had over tape and LPs. It didn't take much for a salesman to add "Now imagine a picture 60 percent sharper than video tape to go along with that sound!"

Out of the dozens of video disc formats contemplated in the seventies, only the optical disc survived in the consumer market. The issues surrounding the creation and ownership of optical storage mediums are complex and multilayered. A success creation has many fathers, while a failure has none. Given the millions to be had in royalties, I'm sure there will be others that will claim to be the disc daddies, while others will simply want to dismantle Pioneer's preeminence in licensing for their own reasons.

The story of optical storage is not just the tale of new technology, but a microcosm of what is good and bad about the corporate system. Creative souls often make lousy businessmen. There are a few exceptions. Walt Disney was one of them, Thomas Edison another. T he competent engineer is usually more caught up in the momentum of discovery than the desire to protect capital gains. this is a fact certainly not lost on any enterprising entrepreneur. The ethical person is a sitting duck for a man whose only God is money. T here are many connected with the creation of optical storage systems that may never be given full credit for their contributions.

Preserving the Past

The incredible part is that none of the corporations involved with the development of optical storage

seems to have much interest in preserving the past. During the celebration of MCA's 75 years in the entertainment industry,

|

Colleen Benn, Vice President, Videodisc Products

Universal Studios Home Video |

PR releases proudly hailed 1981 as the year the company ventured forth in the home video market with the release of some

twenty-odd pre-recorded videocassettes - completely ignoring the 1978 debut of DiscoVision. DiscoVision was such a

horrendous PR nightmare for MCA that most there are happy about the fact that the average disc consumer knows nothing about

it. After the 1996 Northridge Quake in California, some 4,000 sets of forgotten DiscoVision turned up in a quake damaged

MCA warehouse. Despite repeated attempts on my part to salvage and catalog these pieces, MCA/Universal Home Video Vice

President Colleen Benn could think of nothing better to do with these items than order them destroyed as painful reminders

of a time best forgotten.

Philips, on the other hand, promotes itself as the inventor of disc technology whenever convenient,

but by-passes the corporate fiasco that was known as Magnavision. The average person is under the impression that the medium

begins and ends with Pioneer, a fiction that Pioneer enjoys fostering whenever it can.

At various times I have had the ears of both MCA and Pioneer in my attempts to gain funding for

further research, establish an archive and have a documentary filmed using those still around. Pioneer ultimately only

wanted to see what research I had that might hurt them, while the executives at MCA, sympathetic to what I was trying to

accomplish, all departed shortly after Peter Broffman's take over of the company.

One executive with DiscoVision Associates, who was sent to negotiate possible funding by DVA,

told me the company spent more on their Xerox bill in three months than what I was asking for to document their history.

However, DiscoVision Associates is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Pioneer, not really interested in preserving the past

that has nothing to do with them directly and extremely paranoid that continued research into the roots of optical storage

might jeopardize their position as licensing czar. The talks with the suits at DVA concerning funding ultimately turned

out to be nothing more than a fishing expedition by the lawyers to try and get a cheap look-see at what I had.

Conclusion

For me, I'm not the type to fall in love with technologies. I am a sculptor by trade, not an

engineer. I make wax figures for museums. I can spend months and hundreds of dollars trying to track down appropriate

reference photographs to sculpt from. My professional life changed forever when I hit Still Frame on an old CAV

DiscoVision copy of Saturday Night Fever playing on a Pioneer LD-660. Here was a technology that gave me a

private sitting with any well known personality captured on film. I love this medium.

My hope is that this article will spark some archival activity within the optical storage